The Four Tendencies

How you respond to expectations tells you how likely you are to follow-through on a commitment to yourself or to others.

It can feel like slow-motion. Watching yourself act against your own self-interest, questioning why you are doing the opposite of what you said you wanted.

If you’ve ever struggled to meet expectations (your own or other people’s), you know how frustrating it can be to watch others around you simply ‘do the thing’ while you wonder why you can’t.

And if you are the type who consistently meets expectations, you might question why so many around you can’t seem to ‘do the thing’. Why make life more difficult when you can just follow-through on your commitments?

For a long time, I struggled to understand why I was so inconsistent with follow-through. If it was for someone else, like meeting a deadline or showing up to an appointment, I would do it. But as soon as it was for me, like waking up earlier or going to the gym, I would inevitably tell myself, “I’ll start tomorrow”. I envied those around me who effortlessly made their own plans and stuck to them.

So when I learned the Four Tendencies framework by Gretchen Rubin, it felt like someone turned on a light in a dark room. I could finally see a consistent pattern of struggling to take action on some things but not others. And even though I wasn’t thrilled about my tendency, the Obliger, I felt seen and less alone.

Understanding the Four Tendencies doesn’t just explain patterns of behaviour, it also provides strategies for each tendency, tips to communicate effectively with other tendencies, and offers perspective when taking advice from others.

What is it?

The Four Tendencies framework is all about how you respond to expectations.

- Inner expectations: those set by yourself, for yourself, like deciding when to wake up, when to exercise, setting up a project timeline for your own work, etc.

- Outer expectations: those set by another person or outside force, like attending an appointment, meeting a deadline, showing up to a class, etc.

In both types, there is an expectation of what action you will take and how you will implement it. Whether it’s an inner or outer expectation depends on who sets the expectation.

The tendencies are based on how you respond to each type of expectation.

- Meet expectations: you tend to take the action as expected

- Resist expectations: you tend to resist taking the action as expected

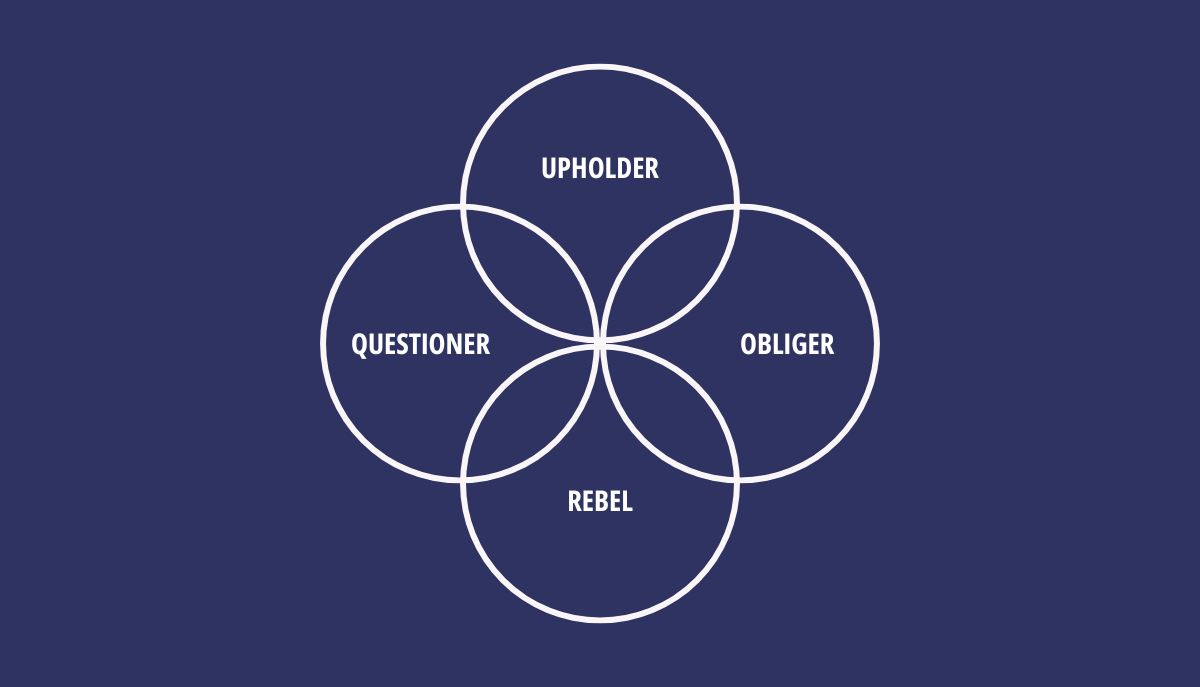

The four possible combinations give us the Four Tendencies:

- Upholders tend to meet both inner and outer expectations

- Questioners tend to meet inner expectations, but resist outer expectations

- Obligers tend to resist inner expectations, but meet outer expectations

- Rebels tend to resist both inner and outer expectations

Note: The use of the word “tend” is intentional and important. Any of the Four Tendencies can act against their type. An Upholder can resist expectations, just like a Rebel can meet expectations. It’s not definite and rigid. A tendency is exactly as it sounds—something we tend to do in most cases.

Upholder

With the Upholder tending to meet both inner and outer expectations, it can appear like they have the best of both worlds. If they say they are going to do something, they do it. If they are expected to do something by someone else, they do it.

They are reliable and self-guided, and they gravitate towards structure. The high structure is an advantage, however, it can become a problem if the Upholder clings too rigidly to the structure even when it’s no longer necessary. Rubin refers to this as “tightening”. In this case, the Upholder struggles to let go despite having negative impacts on other areas of their life.

Rubin offers the example of someone who starts coming to work 2 hours earlier to meet the deadline of a major project, only to have them continue the earlier start time after the project has concluded and is no longer necessary. They may decline personal invitations for evenings in order to stick to an earlier bedtime or miss out on opportunities for breakfast with their family.

Since the Upholder tends to readily meet inner and outer expectations, they can struggle to understand why many others can’t seem to do the same.

Questioner

The Questioner tends to meet inner expectations and resist outer expectations, so they are also self-directed types. Although they tend to resist outer expectations, it depends on whether the expectation is aligned with their inner expectations or not. If a Questioner is asked to do something they would also expect of themselves, it becomes an inner expectation, and they meet it.

The Questioner focuses heavily on justification and takes time to understand the rationale of what is being asked by themselves or others. “Why am I being asked to do this? What’s the purpose? Does this make sense?” Their instinct is to question any external expectation as soon as they are asked. Although the intention of the Questioner is to understand what is being asked and why, it can come off to others as unnecessarily combative.

Questioners struggle with expectations they perceive as arbitrary. If there is no clear purpose, they wouldn’t expect it of themselves, so why should they be expected to do it by someone else? Occasionally, they will find themselves is a situation where the expectation may be arbitrary but has negative consequences if not done (e.g. risk losing their job). At these times, it’s helpful to tap into the greater purpose, like valuing your job more than arguing the nature of the request.

Questioners also run the risk of analysis paralysis. While this can happen with any tendency, Questioners can often find themselves unable to take action until they have enough information. To combat this, it’s helpful to use guardrails like a time-limit for research, or deferring to an expert who has done the research already.

Obliger

The largest group of the four, Obligers tend to meet outer expectations but resist inner expectations. They are reliable to others, but not to themselves. Of all the tendencies, Obligers can be the hardest on themselves as they can be trusted to do what’s expected by others while regularly blowing off their own commitments.

Because of this, Obligers are often asking themselves, “Why can’t I seem to do what I say I’ll do? Why can’t I be more like [Upholder/Questioner]?” The resistance to their inner expectations is typically contrary to their genuine desires, so it feels like self-sabotage.

Also, due to their reliability and regularly meeting expectations of others, Obligers tend to be the ones taking on volunteer roles or extra responsibilities. Unfortunately, this can lead to other types taking advantage of Obligers’ willingness to rise to the occasion. Rubin explains a phenomenon called “Obliger Rebellion”, in which an Obliger suddenly acts against their usual tendency and stops meeting commitments to others. This dramatic shift can surprise others, and sometimes the Obliger themselves, although it often comes from resentment that has been building over time.

The best strategy for an Obliger to meet inner expectations is by turning them into outer expectations. By using external accountability, they can play to their strengths. It can feel frustrating that this is the case (I speak from personal experience), but acceptance is key. Many Obligers have wasted valuable time wishing they were more like Upholders and Questioners, but it won’t change their tendency.

Rebel

The smallest group of the four, Rebels tend to resist inner and outer expectations. They don’t want to be told what to do by others or by themselves. Even if they want to do something, as soon as someone else expects it, their instinct is to rebel. It doesn’t mean they can’t meet expectations, it just means resistance is usually the first reaction.

Identity plays a key role for the Rebel. Although they resist inner and outer expectations, they can connect with an identity consistent with their values. For example, a Rebel who connects with the identity of a person who values health and longevity can adopt and stick with a consistent fitness routine and diet regardless of what’s ‘expected’ of them. Or a Rebel who values growth and improvement may work with a coach or mentor, showing up to calls not because it’s expected, but because it’s who they are as a person.

Like Obligers, Rebels can struggle with the sense of self-sabotage by not following-through on inner expectations. It’s not just that they resist inner expectations, it can be made worse the moment someone else ‘expects’ it. Sometimes a mere suggestion is enough to rebel.

The Rebel places a high value on freedom and doesn’t want to be controlled. So the instinct to resist being told what to do makes sense on the surface, but always doing the opposite of what’s expected is not freedom at all. True freedom for the Rebel is pausing long enough to ask what they really want regardless of expectations.

What it’s not…

It’s important to remember the Four Tendencies framework is about how people tend to respond to inner and outer expectations. That’s it.

It cannot predict a person’s kindness, creativity, intelligence, integrity, leadership abilities, etc.

You have to be careful about attributing other characteristics to a framework like this because it happens subconsciously. Biases and shortcuts can lead to faulty conclusions, like assuming a resistant Rebel wouldn’t make a good leader, a reliable Obliger who volunteers is kinder than other types, a discerning Questioner is more intelligent than others, or a structured Upholder has more integrity than other types.

These cognitive shortcuts are not just faulty, they can also be harmful. It’s easy to make inaccurate assumptions about a person’s character or value with broad strokes.

Why it matters

Understanding Yourself

Understanding how you respond to expectations helps you work with your strengths and limit negative outcomes:

- Upholders can be on alert for tightening and let go of routines that no longer serve them

- Questioners can use guardrails to avoid analysis paralysis, and when an outer expectation feels arbitrary but consequential, to connect it to a greater purpose

- Obligers can turn inner expectations into outer ones through external accountability, and practice boundaries to avoid saying yes too often (leading to resentment)

- Rebels can connect to identity instead of expectations, and be on alert for the impulse to do the opposite of anything someone asks of them, taking a pause to ask what they really want

These strategies are tailored to the tendency, working with the type instead of against it. Working against your tendency is like swimming against a current. Sure, you could do it for a bit, but soon you will be exhausted and run out of steam. Choosing a strategy based on your tendency is like swimming with the current. You are still making an effort, but you get farther with each stoke and can swim longer.

For a long time, I wasted time and energy wishing I could be more like the Upholders in my life. “If I could just be more like her…” All it did was add to my existing shame and feed into the cycle of frustration. So once I learned my tendency, it finally made sense why my efforts to meet inner expectations usually failed while I rarely struggled with outer expectations.

To be clear, I’m not thrilled with my tendency—far from it. Do I occasionally envy others who can meet inner expectations with ease? Yes, I’m human. But when it happens, I remind myself to stop fighting reality. Swim with the current. Use the strategies that work. And put that energy to good use.

Understanding Others

Once you understand the four types, you can also start to better understand those around you. Knowing this can help you adapt how you communicate with others, especially if you are asking something of them.

You may not have a lot of trouble asking something of an Upholder or Obliger, who both tend to meet outer expectations. But asking a Questioner or Rebel is a different matter.

- Questioners: Address their desire for justification by providing rationale. If there is no clear rationale, you may have to tap into a bigger purpose.

- Rebels: Since a Rebel’s instinct is to resist being asked to do anything but they can connect with identity, it can help to frame the request so it connects to their values. Also, since Rebels value freedom, it can help to let them have some freedom with how they do their work.

It’s also useful in group settings to check-in and see if Obligers are being unfairly burdened with outer expectations from others in the group, like in a work setting where extra responsibilities fall most often to Obligers.

Who’s Giving the Advice?

Before Gretchen Rubin wrote The Four Tendencies, she wrote a lot about habits. She didn’t know it yet, but she was an Upholder who rarely struggled to meet an inner expectation once she decided to take action. So she was genuinely confused by so many of her readers asking, “But how? How do you get yourself to do it?”

In Rubin’s case, her confusion led to curiosity. She explored how people react to expectations and developed the Four Tendencies framework.

But many who teach habits and productivity may have a blind spot about how their tendency influences their advice. It’s understandable that Upholders and Questioners who follow-through on their inner expectations would expect others can do the same. The issue is when the advice-giver presumes it will apply equally to everyone. So when advice doesn’t work for an Obliger or Rebel, it’s seen as an individual failing to follow the advice instead of the advice failing to suit the individual.

Being familiar with the Four Tendencies enables you to better assess advice from others.

- Is it applicable to your tendency?

- Can it be adapted to suit your tendency?

You’ll become a better judge of what will work for you and what you can ignore. And I don’t just mean ignoring advice. You can also ignore any judgement that may accompany the advice. I’ve watched well-meaning experts judge a person’s inability to follow-through on inner expectations, implying a lack of discipline, commitment, or integrity. When this happens, I remind myself we’re all wired differently… even the person giving the advice.

Common questions

How do I figure out my tendency?

If you are not sure which one fits, you can take the quiz by Gretchen Rubin or read her book, The Four Tendencies.

Can I be more than one tendency?

Rubin suggests each person has their tendency, but can tip towards one of the adjacent types.

- An Upholder can tip towards Questioner or Obliger

- A Questioner can tip towards Upholder or Rebel

- An Obliger can tip towards Upholder or Rebel

- A Rebel can tip towards Questioner or Obliger

For example, an Obliger will usually meet outer expectations and resist inner, but an Obliger who leans towards an Upholder may be better able to meet some inner expectations, whereas an Obliger who leans towards Rebel may find themselves resisting some outer expectations more often.

The book goes into more detail about each variation.

Can I be both a Questioner and an Obliger?

A lot of people hear the descriptions and feel like they are a mix of Questioner and Obliger, although these two are opposites. Usually, this is one of two things:

- You are an Obliger who asks a lot of questions. You may identify with the description of the Questioner who wants to understand exactly what’s expected and the rationale. The key difference is your instinctual reaction when asked to do something by someone else. Questioners feel automatic resistance while Obligers usually don’t have that instinct.

- You are a Questioner who resists some inner expectations. Any of the four types can struggle to meet an inner expectation, including Upholders and Questioners. This is usually because you are facing a psychological roadblock. It’s about holding yourself back to protect from experiencing a negative outcome, often based on a fear that’s unconscious. More research won’t fix the issue—it requires adjusting your Mindset.

Interested in how you can apply these kinds of concepts to help you find your own momentum? Join the newsletter to stay connected.